| Date 16-Jul-2021 to 16-Jul-2021 |

Location Gurugram, India |

Format Local |

What and who defines ‘man’ and ‘woman’?

A participatory learning session on Understanding Sex and Gender was held with 43 women domestic workers and 7 adolescent girls in Harijan Basti, Gurugram on 16 July 2021 as part of the Sapne Mere Bhavishya Mera program. The objective of the session was to build practical understanding on the term sex (prakartik ling) and gender (samajik ling) so that gender stereotypes and gender roles can be analysed and demystified.

Arrangements for the session was organised by Sarita, a domestic worker champion associated with PRIA’s work in this community for the past four years. She laid out mattresses and tied saris to makeshift poles for shade. Following Covid-19 protocols, sanitiser and masks were made available for the participants. The women who attended the meeting were mobilised by a group of seven domestic workers from the community through phone calls and home visits.

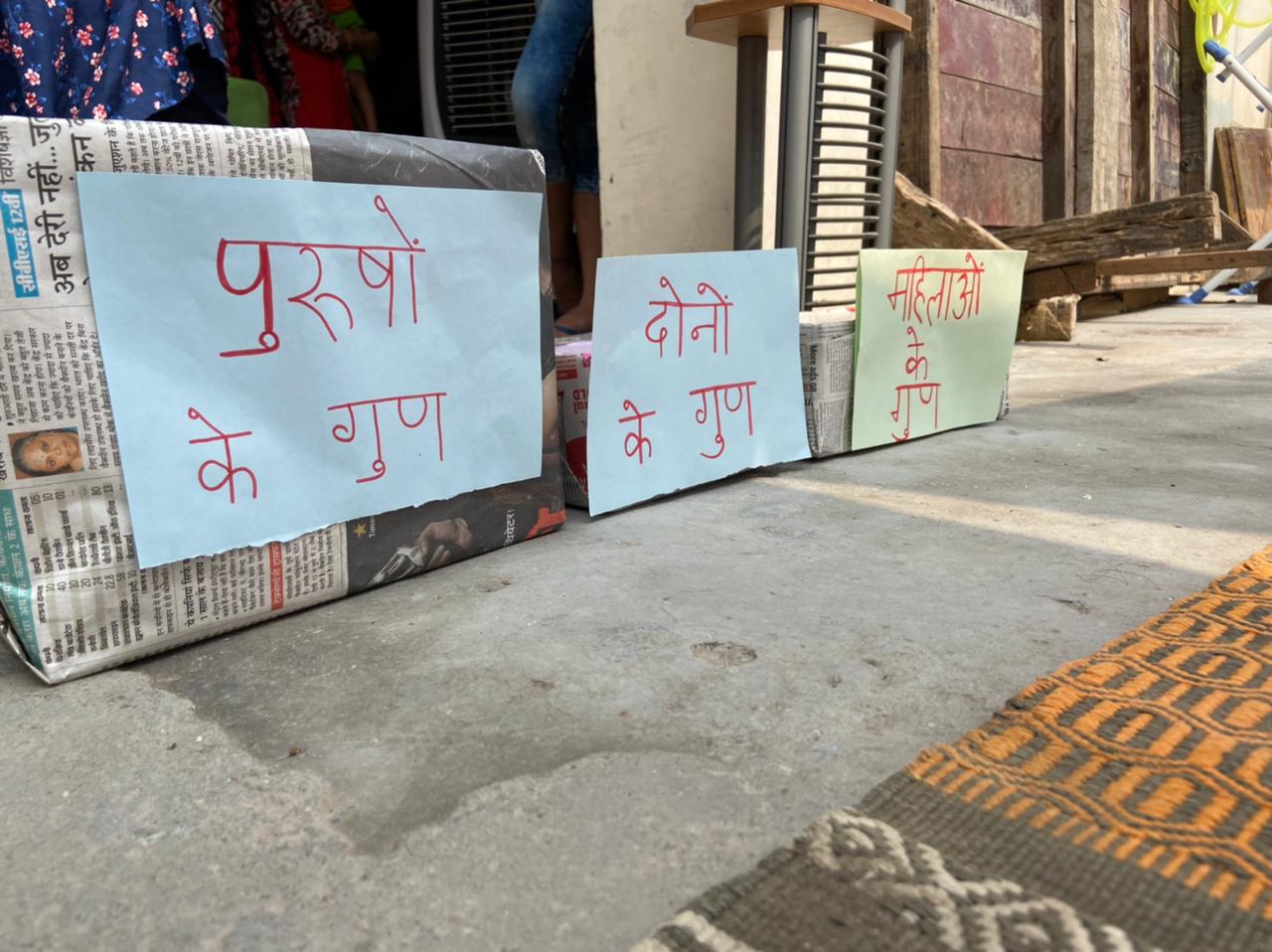

The session started with an activity where women had to choose in which box they would put adjectives/qualities/professions written on place cards. Three boxes labelled ‘Mahilao ke gun’ (women’s qualities) ‘Purushon ka gun’ (men’s qualities) and ‘dono ke gun’ (qualities of both) The 25 place cards on which the adjectives were written were called out and shown to the women, and they decided which box each place card should be put in.

Classification of the words by the women domestic workers

|

Mahilaayon ke gun |

Purosho ke gun |

Dono ke gun |

|

Nurse |

Zimmedar (responsible) |

Doctor |

|

Dayalu (caring) |

Kathor (tough) |

Nirnay lena (take decision) |

|

Kamzor (weak) |

Driver |

Gussa (anger) |

|

Hasmukh (cheerful) |

Paise kamana (earns money) |

Jeans |

|

Lambe baal (long hair) |

Cook |

Samjhdaar (responsible) |

|

Nazuk (delicate) |

Tairaak (swimmer) |

Teacher |

|

Sundar (beautiful) |

Balwaan (strong) |

|

|

Sharam (shame) |

Rakshak (protector) |

|

|

Samvedansheel (sensitive) |

|

|

The choices led to debates and discussion regarding gender roles. Some of the women related to all the 25 adjectives, even if they thought they may not possess the quality. The women veered towards identifying girls/women as docile and sensitive, and boys/men as strong and tough. “Yeh achaa nahi lagega agar ladki log nazuk or samvedansheel nahi hogi” (It doesn’t look good if women and girls are not fragile or sensitive), said Meera.

The choices made by the older women related to traditional gender roles and how society (under)values women. “Hum kitna bhi kaam kar le, bahar ka hamara kaam utna important nahi hain jitna ki purosho ka hain” (It does not matter how much outside work we do, men’s work is always more important than ours).

Younger women had counter-views. “Yeh galatfehmi hai ki mahilaayon ka kaam chota hain, hamara kaam bhi utna hi mahatavpurn hain” (This is a misunderstanding if people think women’s work is less important... we are equally significant).

“Main koi nazuk nahi hu, mujhe sakht banna pada mardo ke jaise” (I am not fragile. With time I have become as tough as men), said Rojina.

The comparison, though, still remained in relation to men.

When asked, “Who decides these gender qualities and roles?”, the majority answered “purwaj” (ancestors) and “bhagwan (god).

A few voices said, “Hum log” (Us).

This led to a discussion on how gender-based differences are made by social norms, sanskaar (culture) and “what our ancestors have taught us”. The participants, several of whom are economically independent women, managing their homes and raising their children as single parents, still remained under the yoke of patriarchy, fitting their behaviours to what society, their families and neighbours will find acceptable.

The session ended with the facilitator explaining the difference between ‘sex and gender.

The women showed willingness to unlearn their understanding of gender stereotypes, and learn the underlying causes for this deep-seated socialisation of gender roles. It was motivating to see the women domestic workers participate in the discussions.

Developing attitudinal and behavioural change is a long journey and women domestic workers have started walking on that path. They go to work, and earn a living. They intentionally or unintentionally are challenging stereotypical gender roles, such as “the man of the house is the breadwinner”, in their daily lives. By questioning themselves and the existing social structures they have shown willingness to change their attitudes.